Blog

Insight + Analysis

When it comes to language, if enough of us are wrong, wrong is right

I saw the musical “Matilda” a lot in March. My daughter was in her school production, and after years of theater, she likes to surprise us on opening night, so we sometimes go into her shows without knowing much about them. Which is to say … I was not expecting a language truth bomb in the middle of “Matilda’s” penultimate showstopper.

If you haven’t read the book, seen the movie or listened to the show: Matilda is a precocious little kid with not-nice parents and an even worse principal whose one goal in life is to crush kids’ spirits. And (spoiler alert) those kids fight back.

Their Les Mis-esque revolution comes after a spelling test that’s rigged to land them all in “chokey.” But instead of being scared, they band together to spell every word wrong. Because if they’re all wrong, their principal can’t punish everyone. I’ll skip the in-between, but they claim their victory and break into the song “Revolting Children.”

And that’s when this line caught my attention: We can S P L how we like! If enough of us are wrong, wrong is right.

The dictionary is VERY proud of you right now, kids. And—being the embarrassing editor mom I am—I seized the moment for an impromptu language lesson with my 11-year-old.

“Did you know the dictionary is DESCRIPTIVE, not PRESCRIPTIVE???” I excitedly shouted at her. She rolled her eyes and walked away. Which is weird, because the dictionary is really cool.

No wait, it really is: Contrary to popular belief, the dictionary doesn’t really tell us how to do anything. Instead, it describes how people are already spelling and using words. It’s a living, evolving collection of how language is used, how it changes over time and how it’s trending in popular culture. It’s very much a historical record documenting English’s growth—and sometimes society’s whims.

Those kids were on to something when they shouted “We can S P L how we like!” They sure can, and if enough of them do it, there’s a decent chance those wrongs will become right.

You might remember a little social-media uproar when Merriam-Webster updated the definition of “literally” to mean “figuratively.” Well, society, that’s on you: You consistently used “literally” to mean “figuratively.” And the dictionary was watching. So when it became clear that the new, evolved use was here to stay, Merriam-Webster added it to its 2013 updates. Because if enough of us are wrong, wrong is right.

A dictionary lexicographer once told me that copy editors (and writers) need to consistently use the styles they like—because we’re the gatekeepers. When we let language through, we’re normalizing it and building the argument for change. There are dozens more prominent examples of English’s evolution in just the past few decades:

Impact doesn’t just mean “to strike.”

“I couldn’t care less” sometimes means you could.

“lol” is on the record books.

Singular “they” is officially here to stay.

Even “literally” started out meaning “figuratively” before it flip-flopped its way back.

It can be hard for writers to let go of the rules that happened to exist in the moment they were taught. And we know all too well how easy it is for readers to hop on Twitter and tell us we’re wrong. But the words, phrases and even grammar “rules” we were taught in gradeschool were never set in stone. Sometimes they never really existed at all.

(Did you catch that one? “Grade school” is two words in the dictionary, but I like it as one. And you probably read right over it without any confusion. Consider this my official petition, Merriam-Webster.)

The thing is, even if you get a little itchy thinking about changing those drilled-in rules, all of this is great news for writers and readers. It lets us flex our creative muscles, try on new phrases and push the boundaries of what our language can do. Sometimes it lets us have fun. Other times it allows us to speak to readers on their own terms. And lately, it’s opened the door for more inclusive language.

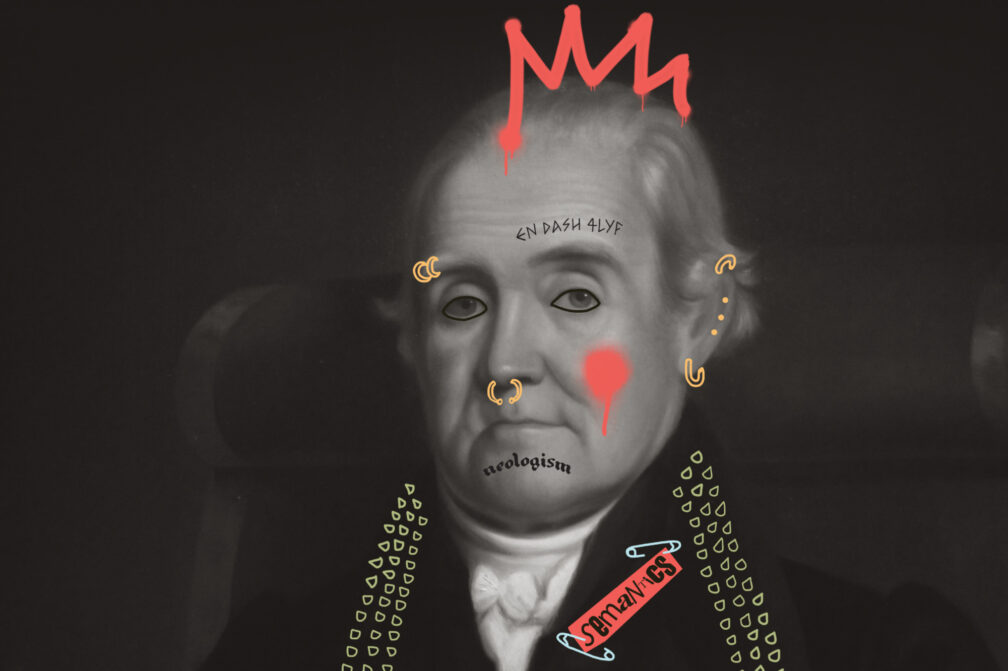

So maybe all of this means sometimes making two words one, adding one serial comma in a sea of simple lists, or throwing caution to the wind and using a hyphen instead of an en dash. Whatever that rule-breaking, language-evolving choice is, if it helps get your reader from point A to point B more clearly than the “rule” would, it’s a good change. It might even make the dictionary take a second look.

And remember, even those cute kids from “Matilda” know what’s up: It is 2 L 8 4 U—E R E volting!

Jen Moritz

Jen Moritz is DS+CO’s senior editor + inclusive language specialist with a passion for the right words and thoughtful, intentional language.